It’s not at all uncommon to open a code repo and find the following commit messages:

version bumpfixed a bugthis works now

These are fine commit messages, but only for one person and at one point in time: the committer and the 5-minute period following the creation of the commit.

Anyone needing to find the source of a change outside of that small window, including said person, is going to have a real tough time. How many commits titled “version bump” are there? What version is it going to? What library are we even bumping the version of? These are all questions some future developers may have to ask because of a poorly-chosen commit message.

Tell A Story

Commits, like the code they describe, should tell the story of the repository. The following is an example of the type of detail a repository story (Reposistory? ™!!!) will tell:

01/02/2020: 'Sample Project' was set up

01/02/2020: project was renamed to 'The Next Next Facebook'

01/05/2020: 'Carbon' date library was installed

01/07/2020: ability to 'Like' comments was added

01/14/2020: database settings were switched to 'PostgreSQL'

01/14/2020: Redis caching was enabled on production only

01/15/2020: homepage logo was added

01/18/2020: Feed will now autoload new comments

If we contrast that against what a lot of repositories look like, the “story” gets considerably less clear:

01/02/2020: init

01/02/2020: rename app

01/05/2020: install lib

01/07/2020: add comment likes

01/14/2020: switch db

01/14/2020: add caching

01/15/2020: new logo

01/18/2020: autoload comments

A lot of detail is lost when telling the story this way; detail that can be important.

Trouble

Say it’s been two weeks since the “add comment likes” commit was created. One of our new developers is handed a task to investigate reports of an issue over the past few weeks where comment Likes are not updating. Inquiring further, they find that the issue occurs not on the feed, but on the user profile page. They are able to replicate the issue but aren’t familiar enough with the code so they decide to review what’s changed in the past few weeks. Loading up our example “bad” commit log, they see a few possibilities:

- Perhaps it could be an issue with the new autoloading comments feature.

- Perhaps something changed that caused new comment likes to not be stored in the database.

- Perhaps the database is being used as the cache and comment “Likes” are not being cached properly.

Our developer decides that the easiest one to rule out is the database. They load up a copy of pgAdmin and check the comments table. There are new comments from the past few minutes so possibility #2 has been ruled out. Our developer then checks for a cache table but doesn’t find one. Possibility #3 has also been ruled out.

Still suspecting a caching issue, the developer decides to find out how caching is being done. They discover Redis is the caching engine and dive into the code. The comment Likes appear to have been cached under a different tag than the comments themselves and using different settings. The cache expiry for Comment Likes on the User Profile was (seemingly mistakenly) set for 60-days in the future instead of 60-minutes. Whoops!

Detail

Going back to our commit message examples we can see a few things right away. The first is that the “good” commit messages give our developer a lot more with which to work. It would’ve told them that a) Redis was the caching engine (ruling out Possibility #3) and b) the new autoloading feature (Possibility #1) only applied to the Feed, not the Profile page where the issue was reported. The environment that Redis was being used on might also have been something helpful that could be discerned from reading the commit messages.

All of this knowledge could narrow down the scope of the investigation without much effort being required of the committer.

Good Storytelling

As with any skill that’s worth doing, being a good storyteller takes time, effort, and practice. Let’s dive into some starting points for telling a good reposi-story.

Be Specific

As we learned in our example above, being specific about what changed can be hugely helpful in finding changes weeks, months, or even years later.

- What version was the library updated to?

Update Carbon library to 2.0.1 - What caching engine was installed?

Create 'Memcached' cache Docker container - What was the memory limit raised to?

Double Pipelines memory limit to 1024MB - What library is being removed?

Remove MomentJS - Which developer’s key is being added?

Add Goldie Wilson ssh key

Use Present-Tense, Active Verbs

There is an adage that I heard early in my career that I encourage everyone to follow: Use present-tense, active verbs to complete the following sentence when composing commit messages: “Merging this code will…”

- Merging this code will…

_Update_ the company logo to the 2020 version - Merging this code will…

_Add_ a new table for phone number verification status - Merging this code will…

_Remove_ support for TLS 1.0

Thinking about completing that sentence helps commit messages to be clear and concise.

Break It Up

This one will easily be the most difficult for some people. Chunking your work into bite-sized commits is not easy to do when you’re working on a long-running feature or refactoring an old one. We’ve all been there when you’ve worked hard to get your code clean, tests passing, and just want to be done. The temptation is to just throw all of your work into one big commit and push it out. After all, nobody needs to know why you touched all of these files and hardly anyone reads them, right?

While certainly tempting, it can cause a couple of issues:

- It makes it more difficult to back out specific changes if needed. Knowing that backing out one slice of work will also take out three others makes more urgent changes difficult.

- If you’re following the principles for writing good messages, it can force you to write really long commit messages (e.g.

Added a new table for phone number verification and added a new controller for phone number management and ...). This also makes it harder to parse when looking through the log.

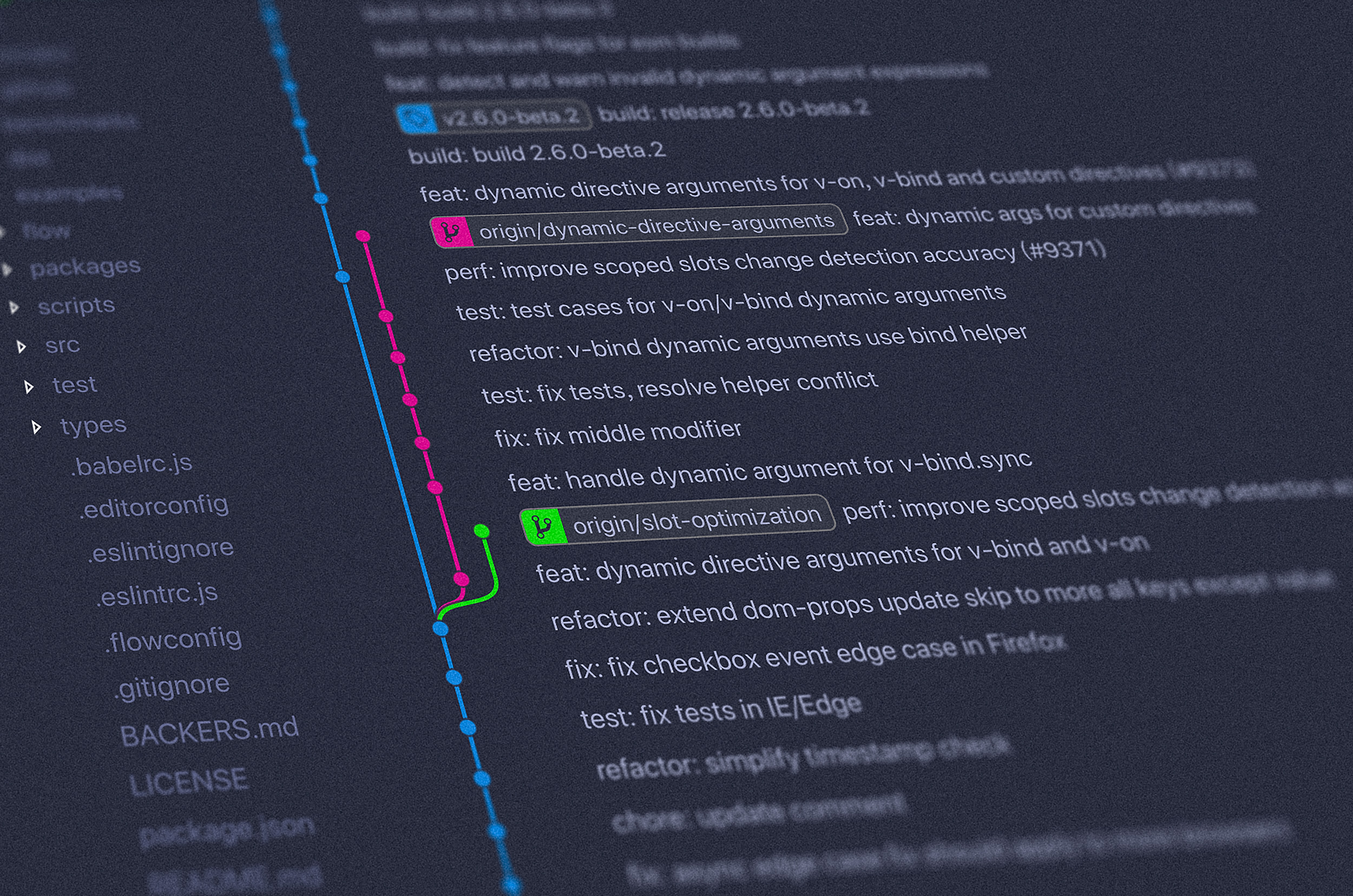

Breaking your commits up forces you to think of how changes relate to one another and which things fit with other things. To make this easier, a number of GUI-based code versioning clients (including GitKraken) allow you to select only specific chunks when committing.

Change Log

The final benefit of writing good commit messages that I want to cover is the changelog. When telling a story well, the git log can often be turned into (or at least act as a starting point for) your product changelog. Imagine being asked for the list of changes that will be released this week and finding the following commits from before in the commit log:

01/02/2020: rename app

01/05/2020: install lib

01/07/2020: add comment likes

01/14/2020: switch db

01/14/2020: add caching

01/15/2020: new logo

01/18/2020: autoload comments

As changes often go beyond product requirements, lacking good commit messages will cause you to have to manually chase down each and every change that has occurred since the last release. With our storytelling commit messages, we could easily come up with something like this:

- We have a new name! Generic Product is now The Next Next Facebook!

- Displaying Dates in The Next Next Facebook is now even easier.

- They comment on it, you like it. You can now Like Comments!

- The Database has been upgraded and performance will be even faster!

- You’ll now see our new logo on the homepage!

The person reading through the commit log doesn’t even need to be someone technical if the story that is told is told well.

Caveats

CI/CD

A story was told recently by David Bernstein at the Pragmatic Programmer Conference In The Cloud 2020 event about a company in Seattle. During a tour of said company, they came upon the main developer area where there sat in the corner a large box. When asked what the box was, the guide responded something like this: “That is the build server. See those lights and sirens all around the ceiling? Those go off when someone breaks the build. You don’t want to be the one who breaks the build.”

If your team has a CI/CD build pipeline with a single branch, you may not want to be the one who breaks it. If that is the case, you may have to think more carefully about how you break down your commits. This could especially be the case if you were working on a feature/bug that took a larger amount of time. Without knowing the specifics of your situation, I would still encourage you to break down your commits as best you can in a way that doesn’t break the build.

Squashed Commits

Some teams either automatically, or require developers to manually, squash their commits as they merge them. This might cause some to question the value of writing thorough commit messages when there’s the possibility it could be lost during a squash. Commit messages can be condensed when performing a squash, but that’s outside the scope of this article.

Some hosted VCS services (e.g. Bitbucket) will also auto condense your commit messages into a single commit with the full list of messages attached. But even if that were not the case, I would still recommend you practice good commit message etiquette. Clear commit messages can be helpful during code reviews. You also never know when a branch may go stale, or you just need to find a specific change quickly.

Be Committed

I know it’s not always easy, and I myself struggle with the above tips from time to time. We all tell a story with our commits. What will yours be?